Who Should Make the Online Rules?

This article is part of the On Tech newsletter. You can sign up here to receive it weekdays.

The tech companies had the right to block President Trump from their sites this past week, and to stop doing business with an app where some people were urging violence. And I believe they made the right decision to do so.

But it should still make us uncomfortable that the choices of a handful of unelected technology executives have so much influence on public discourse.

First, here’s what happened: Facebook froze at least temporarily the president’s account after he inspired a mob that went on to attack the Capitol. Twitter locked his account permanently. And then Apple, Google and Amazon pulled the plug on the (almost) anything-goes social network Parler.

Kicking Trump off

Yes, Twitter and Facebook are allowed to decide for themselves who can be on their services and what those users can do or say there. Locking an account that breaks Twitter’s rules is similar to a McDonald’s restaurant kicking you out if you don’t wear shoes.

The First Amendment limits the government’s ability to restrict people’s speech, but not the ability of businesses. And it gives businesses in the United States the right to make rules for what happens inside their walls.

Reasonable people can believe that Facebook and Twitter made the wrong decision to lock Mr. Trump’s account for fear that his words might inspire additional violence. But it is their prerogative to be the guardians of what is appropriate on their sites.

Millions of times a month, Facebook and Twitter delete or block posts or censure their users for reasons ranging from people selling knockoff Gucci products to people trying to post images of terrorist attacks or child sexual abuse. Again, people can quibble with the companies’ policies or their application of them, but having even the most basic rules is important. Almost no place on the internet or in the physical world is an absolute zone of free expression.

The app stores of Apple and Google, and Amazon’s cloud computing service, also are justified in kicking out Parler, an app that became a hub for organizing violent acts such as last week’s rampage. Parler set few limits on what people could say inside its digital walls, but its business partners decided that the app broke their rules when it didn’t act on examples of incitements to violence, include an exhortation to kill the vice president.

Should these companies get to decide?

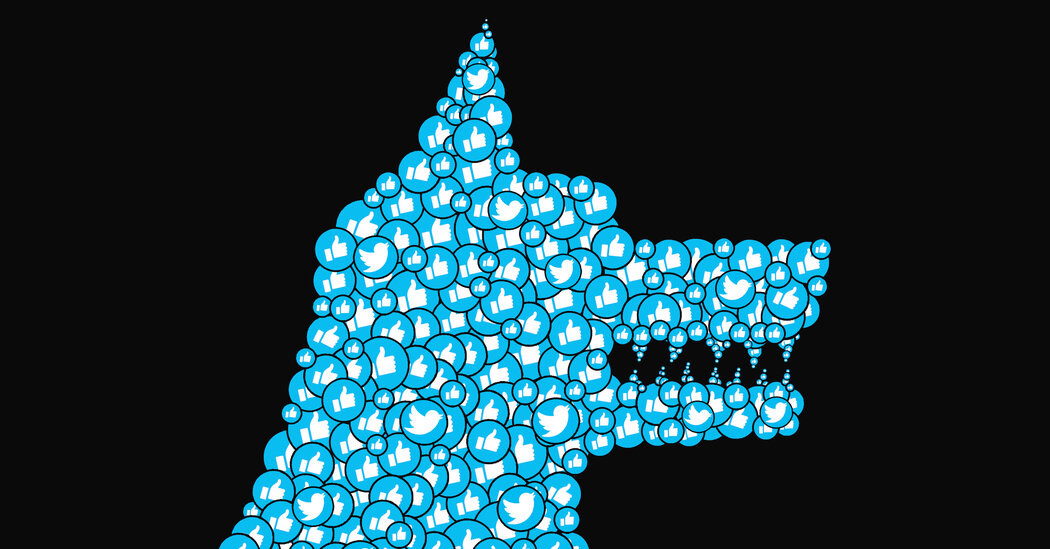

I can think all these tech companies made the right decision in the last few days but still feel extremely uncomfortable that they are in the position of acting as a Supreme Court — deciding for billions of people what is appropriate or legal expression and behavior.

My McDonald’s example above isn’t really equivalent. Facebook and Twitter have become so influential that the choices they make about appropriate public discourse matter far more than whom McDonald’s lets in to buy a burger.

Capitol Riot Fallout

And while these companies’ rules are extensive, they are also capriciously applied and revised solely at their whim.

Plus, as the free expression activist Jillian York wrote, most people have little “right to remedy when wrong decisions are made.”

There has been lots of screaming about what these companies did, but I want us all to recognize that there are few easy choices here. Because at the root of these disputes are big and thorny questions: Is more speech better? And who gets to decide?

There is a foundational belief in the United States and among most of the world’s popular online communications systems that what people say should be restrained as little as possible.

But we know that the truth doesn’t always prevail, especially when it’s up against appealing lies told and retold by powerful people. And we know that words can have deadly consequences.

The real questions are what to do when one person’s free expression — to falsely shout fire in a crowded theater, or to repeat the falsehoods that an election was rigged, for example — leads to harm or curtails the freedom of others.

The internet makes it easier to express oneself and reach more people, complicating these questions even more.

Apple and Google are largely the only places for people to download smartphone apps. Amazon is one of a tiny number of companies that provide the backbone of many websites. Facebook, Google and Twitter are essential communications services for billions of people.

The oddity is not that we’re struggling with age-old questions about the trade-offs of free expression. The weird thing is that companies like Facebook and Apple have become such essential judges in this debate.

Before we go …

-

What happened at the Capitol defies easy explanation: Ben Smith, a media columnist for The New York Times, reflected on a former colleague at BuzzFeed who went from tailoring news for maximum attention online to becoming one of the people who stormed the Capitol last week. This man’s story shows that getting affirmation online “can be giddy, and addictive,” Ben wrote.

-

Fact-checking some of the responses to the tech gatekeepers’ decisions: The Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Jillian York, whom I quoted above, has a useful rebuttal to some of the claims being made about the actions of Facebook, Amazon and other tech companies against President Trump, Parler and others.

-

Tech gatekeepers as conduits of government censorship: Distinct from the choices of American tech companies, large mobile phone providers in Hong Kong appear to have cut off a website used by some pro-democracy protesters in the city. My colleagues Paul Mozur and Aaron Krolik wrote that this step set off fears that authorities may be adopting censorship tactics widely used in mainland China in Hong Kong, long a bastion of online freedom.

Hugs to this

I don’t know why this big and fluffy cat is on a beach. Just enjoy it.

We want to hear from you. Tell us what you think of this newsletter and what else you’d like us to explore. You can reach us at ontech@nytimes.com.

If you don’t already get this newsletter in your inbox, please sign up here.

Comments are closed.